by David Bacon

Capital & Main, November 20, 2020

All photos © by David Bacon. These photos are housed in the Special Collections of the Green Library at Stanford University.

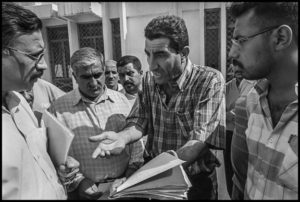

An organizer talks at lunchtime with a D’Arrigo Brothers worker with a union button on her cap.

Not long before Donald Trump’s election in 2016, the Pacific Legal Foundation filed suit against California’s farmworker access rule in federal court on behalf of two companies – Cedar Point Nursery in Siskiyou County and the Fowler Packing Company in Fresno. The foundation is a conservative libertarian group that holds property rights sacred and campaigns against racial equity. It fought hard for the appointment of Amy Coney Barrett to the high court.

The access regulation, which took effect after the passage of the Agricultural Labor Relations Act in 1975, allows union organizers to come onto a grower’s property in the morning before work to talk with workers. According to the labor board’s handbook, “The access regulations of the Agricultural Labor Relations Board are meant to insure that farm workers, who often may be contacted only at their work place, have an opportunity to be informed with minimal interruption of working activities.”

Two UFW organizers walk into a D’Arrigo Brothers broccoli field in Salinas, 1994.

The board requires that the union give notice to the employer before taking access, and that organizers not disrupt work. They can talk only for an hour before and after work and during lunch, and can take access for only a total of 120 days during a year.

Growers have always hated the access rule, and many at first refused to obey. Former United Farm Workers organizer Fred Ross Jr. remembers being arrested several times in Santa Maria for taking access. “This was all about power and who had it,” he says. “Growers had it all, and their workers none. They wanted to dominate. For them, workers didn’t even have the right to talk.”