The U.S. troop withdrawal from Afghanistan should force a reckoning with a long history of military intervention.

By David Bacon

Foreign Policy in Focus | August 30, 2021

View at Foreign Policy in Focus

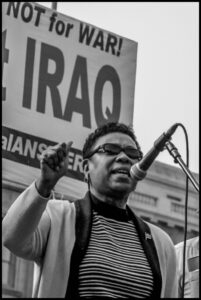

Rep. Barbara Lee (D-CA) was the main speaker at the rally of over 200,000 people who marched up Market Street in San Francisco to protest the Bush administration’s war on terror and threatened invasion of Iraq. (© 2001, David Bacon)

Many in the U.S. media continue to credit the good intentions of the U.S. war in Afghanistan, while belaboring its failure over 20 years to achieve any of them. But to say that the United States wanted a progressive, liberal democratic, and secular government in Afghanistan can only be believed by those who refuse to remember what Washington did when Kabul actually had one.

In the days following the attacks on September 11, the United States was called on to declare war against an enemy those in Congress who voted for it couldn’t even name. Policymakers asked American citizens to sacrifice civil liberties for security and give the military money that was so desperately needed to solve the country’s social problems.

Congress did those things with only one dissenting vote: Barbara Lee’s. Now it’s time to look at historical truth, to understand how the United States got this 20-year war, with its ignominious end at the Kabul airport, and how the overarching framework of U.S. policy was responsible for creating it.

Other countries facing similar traumatic changes wrenching them from the past have pioneered a way to examine their own history. El Salvador, Guatemala, South Africa, and elsewhere established truth commissions to probe into and acknowledge each country’s real history. Such public acknowledgement is a necessary step towards change.

The United States is no stranger to this process. After the end of the Vietnam War (or the American War, as the Vietnamese call it), Senator Frank Church held watershed hearings that brought some of the Cold War’s ghosts to public attention. But the process was cut short, the policies responsible for Cold War atrocities never fully questioned, and as a result, the ghosts were never laid to rest. Those ghosts still haunt the United States, and in Afghanistan hundreds of thousands died for them.

The massive social upheaval at home following the Vietnam War- and the deaths of over a million Vietnamese and 40,000 US soldiers-forced Senator Church’s examination. Before the people of this and other countries pay a similar price in yet another war, the United States need to reexamine that history.

The roots of the terrorist attacks in New York and Washington lie in the Cold War. Without truly ending it and untangling its consequences, there will be no security for us.